The Greek word "Chrysostomos" in the tenth paragraph of Telemachus

compounds chrysos (gold) and stoma

(mouth). Several orators of antiquity acquired this epithet

"golden-mouthed," notably St. John Chrysostomos (ca. 349-407),

a renowned speaker and one of the Three Holy Hierarchs of the

Greek Orthodox faith. The odd one-word sentence appears to

react to Mulligan's "even white teeth glistening here and

there with gold points" in the previous sentence, and by

extension to Mulligan's facility with words. It is the first

appearance in Ulysses of the book's revolutionary

stylistic device of interior monologue, and it

introduces readers to a Stephen who has a lot going on in his

head, not only apart from external reality but in opposition

to it.

Bernard Benstock says of this cryptic one-word sentence, "As

a comment on Buck's dental work it is redundant; as a

narrative comment it is out of place" (Critical Essays,

3). Who is thinking this odd thought? There is only one good

possibility: the person standing next to Buck Mulligan,

watching his moving mouth and listening to his verbal

pyrotechnics. Stephen is the kind of person who can muse on

church fathers before his first cup of tea, and also the kind

of person who would notice that one of Mulligan's middle names

is "St John," linking him with St. John Chrysostomos. And, as

Benstock observes, Stephen repeatedly thinks of Mulligan in

damning one-word judgments: "Usurper"

at the end of Telemachus, "Catamite" in Scylla and

Charybdis, "Chrysostomos" (i.e., glib speaker) here.

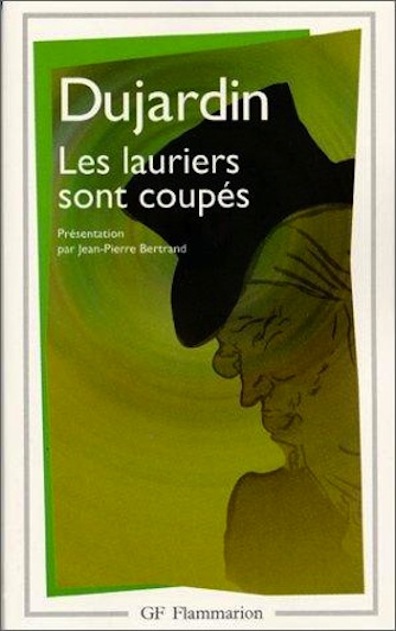

Joyce often said that the minor French novelist Édouard

Dujardin inspired him to present the internal, unspoken

thoughts of his characters in this way. Ellmann tells the

story of how Joyce encountered Les lauriers sont coupés

(1888) and was impressed by the technique of Dujardin’s

experimental novel, an extended soliloquy that totally

dispenses with third-person narration (126). He also quotes

several sayings that evoke the book’s appeal to Joyce. One is

a sentence of Fichte that inspired Dujardin: “The I

poses itself and opposes itself to the not-I.” The

other quotes are Dujardin’s: “the life of the mind is a

continual mixing of lyricism and prose,” and the novel must

therefore balance “poetic exaltation and the ordinariness of

any old day.”

“Chrysostomos” shows Joyce following in these Symbolist

footsteps, opposing inward reality to the outward environment.

The word takes readers for one moment into the fanciful realm

of Stephen’s thoughts where ordinary images like gold and

white teeth become imbued with intellectual significance. The

word defines Mulligan––the "not-I"––as a glib coiner of

elegant phrases who does not use language in the service of

truth. It also affords a glimpse of the "I" that is Stephen,

an ego desperately defining itself in opposition to other

human beings. (People who have read Stephen Hero or

especially A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man are

already familiar with this young man defining reality in his

own way, rejecting all people and institutions who threaten to

warp his understanding of himself.)

The term that Joyce used to describe Dujardin’s

innovation, monologue intérieur, did not originate

with either man. According to Ellmann, Valery Larbaud found

the expression in Paul Bourget’s Cosmopolis (1893)

and gave it to his friend Joyce as a tool for discussing the

author’s big new book (519). Joyce soon felt that the phrase

had outlived its usefulness and went searching for others that

might point readers toward what he was trying to do in the

novel. Nothing better caught on, but his endorsement of

“interior monologue” should at least recommend it over the

comparable phrase “stream of consciousness” that readers often

apply to Ulysses. Only Molly Bloom’s interior

thoughts can justly be called streaming.

[2014] Kevin Birmingham makes this point well in The

Most Dangerous Book: The Battle for James Joyce's Ulysses

(2014). Of the novel's style he writes, “Thoughts don’t flow

like the luxuriant sentences of Henry James. Consciousness is

not a stream. It is a brief assembly of fragments on the

margins of the deep, a rusty boot briefly washed ashore before

the tide reclaims it.”