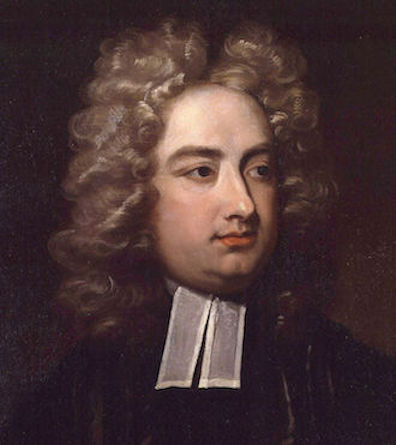

Remembering his time in Marsh's

Library in the enclosure of St. Patrick's Cathedral,

Stephen thinks of the important Dublin-born writer Jonathan

Swift who was Dean of that cathedral from 1713 to 1745.

Stephen casts the "furious dean" as misanthopic and mentally

ill, associating both states with the fictional Gulliver who

would (if he could) have deserted his own species for the

rational horses he met on a Pacific island: "A hater of

his kind ran from them to the wood of madness, his mane

foaming in the moon, his eyeballs stars. Houyhnhnm,

horsenostrilled."

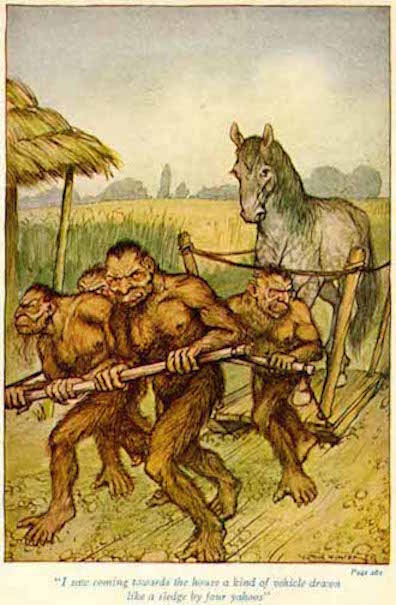

In the fourth book of Swift's Gulliver's Travels,

the protagonist lands on an island populated by filthy,

inarticulate, avaricious, libidinous, and murderous apes

called Yahoos and orderly, logical, serene, selfless, kind

horses called Houyhnhnms. The apes clearly are intended as a

satirical portrait of human beings, as becomes clear when the

horses see the rational Gulliver without his clothes on and

realize with horror that they have been harboring a Yahoo. The

horses strike Gulliver, and many of his readers, as a utopian

alternative to human failings similar to those envisioned in

Sir Thomas More's Utopia and Plato's Republic.

But the horses need not be read so idealistically. In their

feelings (or lack of feelings) about childrearing and mourning

they seem simply inhuman, and their serious consideration of a

proposal to exterminate all the Yahoos associates them with

one of the worst propensities of humanity. Banished from the

island as a lovable but undeniable Yahoo, Gulliver returns to

England, in Stephen's words, "a hater of his kind." He stuffs

herbs in his nostrils to mask the unbearable smell of his own

wife and children, and his only happy moments are spent in the

company of the horses in his stable. Confronted with this

eccentric behavior, the reader who has sympathetically

followed Gulliver's narration cannot help but consider the

possibility that he has lost his wits.

Jonathan Swift was not mad; he suffered from Ménière's

disease. Nor was he completely a misanthrope; as Gifford

notes, he defined man not as a rational or irrational being

but as animal rationis capax, an animal capable of

reason. He hated the irrational mob as much as Stephen

supposes when he imagines him fleeing "The

hundredheaded rabble of the cathedral close," but

he harbored deep, romantic affection for virtuous individuals.

In judging Swift to be a misanthropic lunatic, Stephen seems

to be following some dominant biographical and critical

opinions of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Swift plays a bigger role in Finnegans Wake than in

Ulysses, but Joyce's respect for the great

Anglo-Irish writer remained grudging. Ellmann notes that he

told Padraic Colum that "He made a mess of two women's lives."

And when Colum praised Swift's intensity, Joyce replied,

"There is more intensity in a single passage of Mangan's than

in all Swift's writing" (545n). Nevertheless, by associating

Swift with Joachim of Fiore

("Abbas father, furious dean, what offence laid

fire to their brains?"), Stephen seems to discern

high prophetic purpose in his ravings. In Stephen Hero

he has read an 1897 story by William Butler Yeats, "The Tables

of the Law," that links the two men. The protagonist, Owen

Aherne, says that "Jonathan Swift made a soul for the

gentlemen of this city by hating his neighbor as himself." It

does not seem improbable to connect Swift's uncompromising

moral aspirations with Stephen's own ambition, as he goes off

to exile at the end of A Portrait, "to forge in the

smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race."