Crunching along the shore, tapping shells and sand with his

cane, Stephen thinks, "Sounds solid: made by the mallet

of Los Demiurgos. Am I walking into eternity

along Sandymount strand?" The eternal principles here are

supplied by William

Blake, who conceived of "Los, the creator" as the

earthly form of one of the Four Zoas (the primal faculties),

and by Plato, who conceived of a δημιουργός (demiourgos) or

"creator" that fashioned the visible world. Stephen's idea of

"walking into eternity" was probably directly inspired by

reading Blake.

Timaeus, in Plato's dialogue of the same name, says that a

demiurge formed the world that we see about us. This deity

acts from benevolent intentions in the Timaeus,

fashioning the cosmos to be as good "as possible" (30b), as

much like the eternal Ideas as "necessity" will allow

(47e-48a). Later Gnostic works, by contrast, depicted the

Demiurge as a demon whose creative work is evil, trapping

mankind within the realm of matter. The Platonic position, it

should be noted, is much closer to the Christian view that the

world was made by a beneficent Creator who found his work to

be "good."

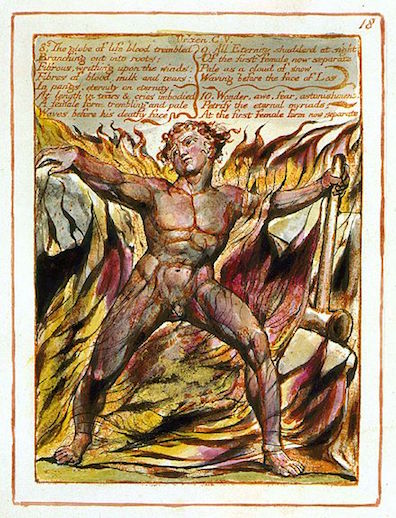

Blake's Los, mentioned in The Book of Urizen, The

Book of Los, America a Prophecy, Europe

a Prophecy (all mid-1790s), and Jerusalem (1804-20),

is also a creator, and like the Demiurge he inhabits an

intermediary plane between the visible and eternal worlds. He

is the fallen human form of Urthona, one of the Four Zoas.

Blake represents him as a smith beating his hammer on an anvil

(associated with the beating of the human heart) and blowing

the fire with large bellows (associated with the lungs). He

creates life, sexual reproduction, and consciousness, and as

the begetter of Adam he originates the line of biblical

patriarchs and prophets.

Thornton notes that, in a 1912 lecture, Joyce referred almost

verbatim to a characterization of Los in yet another of

Blake's works, Milton (1804-10): "For every Space

larger than a red globule of Man's blood / Is visionary, and

is created by the Hammer of Los." In Proteus

Stephen thinks of the things around him having been "made

by the mallet of Los Demiurgos," and he regards that

work as an occasion for "visionary" enlightenment, just as he

drew on the works of Jakob

Boehme and George

Berkeley to read the sights of the seashore as

"signatures" or "signs" of noumenal reality. In Scylla and

Charybdis, however, he associates such hankering after

mystical enlightenment with the hostile Platonists in the

library: "Through spaces smaller than red globules of man's

blood they creepycrawl after Blake's buttocks into eternity

of which this vegetable world is but a shadow. Hold to

the now, the here, through which all future plunges to the

past."

It is hard to know how many of Blake's works Joyce may be

drawing on, but the lecture suggests that at the very least he

was thinking of Milton. That work seems to have

supplied Stephen with his idea of walking into eternity, which

follows hard upon the mention of Los. Blake describes how

Milton entered him through his left foot: "And all this

Vegetable World appear'd on my left Foot / As a bright

sandal form'd immortal of precious stones & gold. / I

stoop'd down & bound it on to walk forward thro'

Eternity" (I, plate 21).

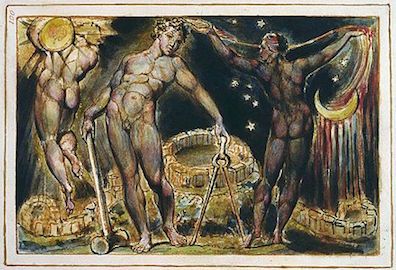

Blake also connects Los with a large pair of compasses,

suggesting the architectonic work of drafting the plan of

creation. In a famous plate, he represented Urizen as the

Ancient of Days extending an opened compass into the dark void

beneath him. Urizen and Los are opponents in Blake's early

works, each trapping the other within a human body. Does their

opposition (constructed as a binary of reason and imagination,

repression and revolution, denial of human passions and

gratification of them) somehow reinstantiate the ancient

debate about the goodness or evil of the created world?

Gifford notes that, "in Gnostic theory and Theosophy," the

Demiurge was called "the architect of the world."

These debates do not surface in Stephen's thoughts, but they

do beg the question of how he may conceive the "Demiurgos":

is it a force for repression and ignorance, or for liberation

and insight? No certain conclusions can be drawn from such

brief utterances, but Stephen's belief that he can access

eternity through the created world does not seem to bespeak a

Gnostic sensibility. It associates him instead with the view

articulated by Plato—and, later, by the early Christians—that

the Creation is good.