Ruthlessly skewering himself in Proteus, Stephen

imagines his writings being rediscovered "after a few thousand

years, a mahamanvantara. Pico della Mirandola like." His

thought seems to have been prompted by reading Walter Pater's

essay on the Italian Renaissance wunderkind

philosopher Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463-94), an essay

which helped to revive interest in Pico's writings in the late

19th century. Stephen's idea, augmented by the Hindu concept

of the "great year," is that people in the distant future will

recognize his genius, even though he went unappreciated in his

own day.

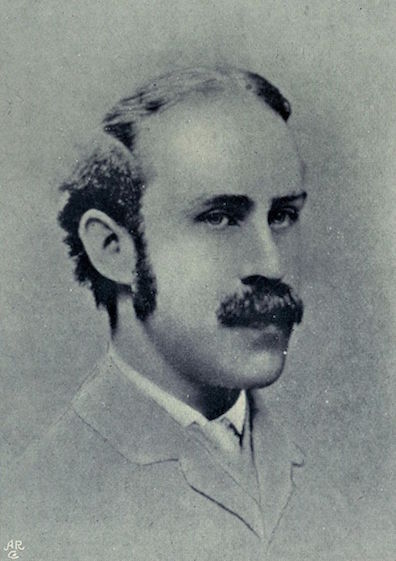

Pico was a humanist scholar with command of four ancient

languages (Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Arabic) and at least some

facility in others (Aramaic, Persian). He set out to recover

all sorts of ancient wisdom traditions, syncretically

harmonizing them with Christianity as inflected by the

Aristotelianism of the Scholastics and the Platonism of 15th

century Florence. Instead of the triumphant reception he

sought by defending his 900 Theses against all

comers in Rome, his teachings were condemned by the pope, his

books were burned, and he lived with perpetual threats to his

freedom and life from the Inquisition. He suffered near-total

obscurity until the last years of the 19th century.

It is easy to imagine Stephen identifying with this

multilingual reader of arcane texts. Pico aspired to transform

European civilization by revealing a radically new but

timeless theology, and he wanted to be recognized as a genius,

like Stephen "stepping forward to applause earnestly,

striking face." Gifford quotes from the biography

written by his nephew Giovanni Francesco Pico, which was

translated into English in 1890: Pico was "full of pryde and

desyrous of glory and mannes prayse." He did not receive such

praise until a Victorian aesthete approached his writings with

the breathless awe of an amateur archaeologist entering a

pharaonic tomb.

Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873), by

the Oxford don Walter Pater, approaches prominent artists and

thinkers of the early modern era (Pico, Botticelli, Leonardo,

Michelangelo, and others) through irreducibly particular

aesthetic responses to qualities like "beauty," "pleasure,"

"charm," "strangeness," "passion," "insight," and

"excitement." The essays in Pater's book seek to capture the

exquisite achievements of a bygone era not through rigorous

historical recovery of past intellectual practices but through

passionate responses in the present.

Pater's prose almost certainly lies behind Stephen's mocking

language: "When one reads these strange pages of one long

gone one feels that one is at one with one who once..."

Thornton quotes a sentence from the essay on Pico that

illustrates Pater's approach: "He will not let one go;

he wins one on, in spite of oneself, to turn

the pages of his forgotten books." Gifford quotes two others:

"And yet to read a page of one of Pico's forgotten

books is like a glance into one of those ancient

sepulchres, upon which the wanderer in classical lands has

sometimes stumbled, with the old disused ornaments and

furniture of a world wholly unlike ours still fresh in them,"

and "Above all, we have a constant sense in reading him . . .

a glow and vehemence in his words which remind one of

the manner in which his own brief existence flamed itself

away." The frequent use of this word appears to have given

Joyce the handle he needed to mock the idea of lost genius

being rediscovered many centuries later.

The "mahamanvantara," which Stephen probably

encountered in Helena Blavatsky's Key to Theosophy (1890

ed.), is a Sanskrit word meaning "great year." It apparently

can be reckoned in various ways, but it invariably totals

billions or even trillions of years. It signifies a time of

cosmic activity, following a mahapralaya or great period of

cosmic downtime. In "The Holy

Office" Joyce wrote that he would not make his peace

with his contemporary Irish writers "Till the Mahamanvantara

be done."

Proteus redirects the barb of this extravagant

thinking to mock the pretensions of the solitary genius.

Stephen's hyperbolic estimation of the time his works will lie

unread is of a piece with his fantasy of sending copies to

"all the great libraries of the world, including Alexandria."