A perforated eardrum. Source: www.durhamhearingspecialists.com.

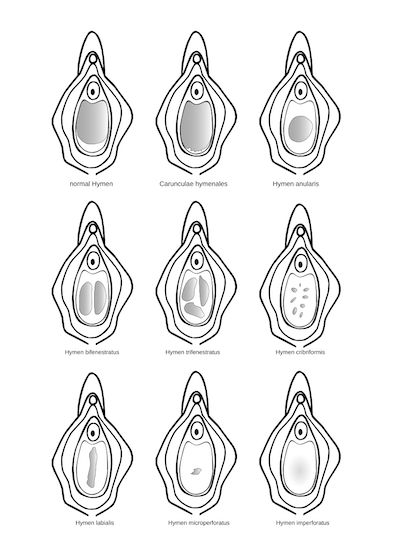

Various types of hymen. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

We

are their harps

In Sirens Simon Dedalus says to Ben Dollard, "Sure,

you'd burst the tympanum of her ear, man...with an organ like

yours," and Father Cowley chimes in, "Not to mention another

membrane." Every element of this lewd joke—the effect of music

on parts of the human body, the libidinal interchangeability

of those parts (throat and phallus, ear drum and hymen), their

transformation into musical instruments (organ,

tympanum)—draws on threads that run throughout the prose

tapestry of the eleventh chapter. Joyce's schemas

identify the Organ of the episode as the ear, but this is far

too limiting. Ears, eyes, lips, cheeks, hands, fingers,

throat, chest, spine, skin, hair, nose, heart, brain, not to

mention penis and vagina—all make up a corporeal symphony

pulsing with sexual energy. Musical instruments play on people

just as people play on them, and just as variously.

Doctors use tympanum, a Latin word for drum, to name

the membrane stretched across the ear canal whose drumlike

vibration makes human hearing possible. That medical usage

provides a chance connection with an instrument in the

symphony orchestra ("The tympanum," evoked in the

chapter's overture), and the anatomical similarity of the

eardrum to the female hymen brings sexuality into the

metaphorical mix. Music enters human consciousness when air

pounds against the eardrum, just as sexual intercourse begins

with a penis pounding against the hymen. Joyce exploits all of

these connections in the joke between Dedalus, Dollard, and

Cowley: Ben's powerful singing constitutes a quasi-sexual

assault on "her" eardrum. Several paragraphs later in Sirens

Bloom recalls the concert in which Dollard was forced to

perform in a pair of borrowed trousers:

Trousers tight as a drum on him. Musical porkers. Molly did laugh when he went out. Threw herself back across the bed, screaming, kicking. With all his belongings on show. O saints above, I'm drenched! O, the women in the front row! O, I never laughed so many! Well, of course that's what gives him the base barreltone. For instance eunuchs.

Basses get their tympanic voices from their male "belongings"

just as eunuchs get their countertenor voices from the

mutilation of these organs, and Molly's wetness in response to

Ben's hilariously revealing trousers suggests a certain female

receptivity. Circe maps the association between

hearing and sexuality onto the Christian story of the Virgin

being impregnated not by semen in her vagina but by words in

her ear. Combining Gabriel's Annunciation with skeptical

stories of Mary having actually been inseminated by a Roman

soldier, the Jewish Virag squawks, "Panther, the Roman

centurion, polluted her with his genitories. (He sticks

out a flickering phosphorescent scorpion tongue, his hand on

his fork.) Messiah! He burst her tympanum."

In a perceptive short essay titled "Joyce's Lipspeech," Derek

Attridge looks at how body parts are isolated in Sirens,

how they seem to act independently, how they substitute

for one another, how they fuel sexual energy, and how they

make music. He observes that the chapter describes singing

voices in terms that suggest sexuality both male ("Tenderness

it welled: slow, swelling. Full it throbbed...Throb,

a throb, a pulsing proud erect") and female ("Gap in

their voices too. Fill me, I'm warm, dark, open") (63).

The "lips" of his title (labia in Latin) "may be a

synecdochic substitute for the whole individual of which they

are a part, but they may also be a metaphoric substitute for

another organ which they resemble. Miss Douce's lips are twice

given the adjective 'wet', and she complains after her

laughing spree, with undecidable reference, 'I feel all

wet'. (Compare this with Molly's 'I'm drenched'...)"

(62).

Vaginal and seminal wetness also enter the chapter in

variants of the morpheme "flow." Bloom thinks about the language of

flowers suggested by Martha's letter, but this word

flows into thoughts of sexual lubricity: "Means something,

language of flow." The language of romantic and sexual

flow-ers has an intrinsic connection to music: "Tenors get

women by the score. Increase their flow. Throw flower

at his feet when will we meet?" In one of the ecstatic prose

responses to Simon's singing of the aria from Martha,

this coincidence of meanings becomes at once fully sexual and

fully musical: "Flood of warm jimjam lickitup sweetness flowed

to flow in music out, in desire, dark to lick flow,

invading.... To pour o'er slucies pouring gushes. Flood,

gush, flow joygush, tupthrob. Now! Language of love."

Many other parts of the body play parts in this symphony of

sexual receptivity. Skin tingles: "Pores to dilate dilating."

Breasts heave: "Full voice of perfume of what perfume does

your lilactrees. Bosom I saw, both full, throat warbling."

Hands stroke: "Cool hands. Ben Howth, the rhododendrons. We

are their harps." Eyes gaze and conceive: "A liquid

of womb of woman eyeball gazed under a fence of lashes,

calmly, hearing." The entire body responds to powerful

music as to sexual excitement: "Braintipped, cheek touched

with flame, they listened feeling that flow endearing flow

over skin limbs human heart soul spine." Attridge

observes that any part of the body can channel sexual energy:

"the sexual innuendos by means of which the two barmaids urge

one another into orgasmic laughter are all achieved by

displacement: 'And your other eye!'; 'With his bit of beard!';

'Married to the greasy nose!' (Lenehan uses the same technique

in his advances to Miss Kennedy: 'Will you put your bill down

inn my troath and pull upp ah bone?')" (64).

By the same principle of displacement, objects that are not

part of the human body also become metaphorically transmuted

into sexual agents. Simon Dedalus fills his pipe as Miss Douce

pours him a drink: "He fingered shreds of hair, her

maidenhair, her mermaid's, into the bowl." Although

Simon does not flirt with Lydia so explicitly and aggressively

as Lenehan, the prose conveys his desire. As he pokes shreds

of tobacco into his pipe bowl, he (or it) imagines another

kind of fingering, another kind of bowl, other feathery

shreds. When Boylan raps on the front door of Eccles Street,

confidently, insistently, Joyce's spectacularly rhythmic prose

turns the knocker into a phallus: "One rapped on a door,

one tapped with a knock, did he knock Paul de Kock with a

loud proud knocker with a cock carracarracarra cock.

Cockcock." As Miss Douce listens to The Croppy Boy,

her hand lewdly strokes the "smooth jutting" tap handle: "Fro,

to: to, fro: over the polished knob (she knows his eyes, my

eyes, her eyes) her thumb and finger passed in pity: passed,

repassed and, gently touching, then slid so smoothly, slowly

down, a cool firm white enamel baton protruding through

their sliding ring."

To call this virtual masturbation would only reduce the

pulsating sexual reverie to dry clinical observation. Sirens

sometimes does speak of sexuality in clinically abstract

terms, as when Bloom gazes on one of the barmaids: "Blank

face. Virgin should say: or fingered only. Write something on

it: page. If not what becomes of them? Decline, despair. Keeps

them young. Even admire themselves. See." But the language

quickly slips back into lubricity, corporeality, musicality: Play

on her. Lip blow. Body of white woman, a flute alive. Blow

gentle. Loud. Three holes, all women." Freud memorably

characterized sexual desire as "polymorphous perversity"—not

just a spur to heterosexual genital copulation but a

promiscuously open-ended energy directed to oral, anal, and

genital gratifications, other parts of the body, other things.

For Bloom, a woman's body is something to play on, an

instrument of different holes and registers to which he might

gently apply his lips.

Sirens is far and away the most consistently sexual

chapter in Ulysses. Exploration of such feelings is

the central organizing element in its imitation of musical

effects. Joyce may have fooled himself and his readers into

believing that his words reproduce the intricately

mathematical structure of a baroque "fuga per canonem," but

there is nothing pretentious about the way he makes language

evoke the fusion of musical sound and corporeal feeling. Music

consists of two kinds of vibrations: those imparted to the air

by instruments, and those introduced via the tympanic membrane

into the bodies of listeners. Just as a lover can play

sexually on a beloved's body, or a musician on an instrument,

musical performances play on every part of the listener's body

and mind: "We are their harps."