The first of the "

Irish

heroes and heroines of antiquity" depicted on the stones,

"

Cuchulin," is surely one inspiration for Joyce's "

broadshouldered

deepchested stronglimbed frankeyed redhaired freelyfreckled

shaggybearded widemouthed largenosed longheaded deepvoiced

barekneed brawnyhanded hairylegged ruddyfaced sinewyarmed hero."

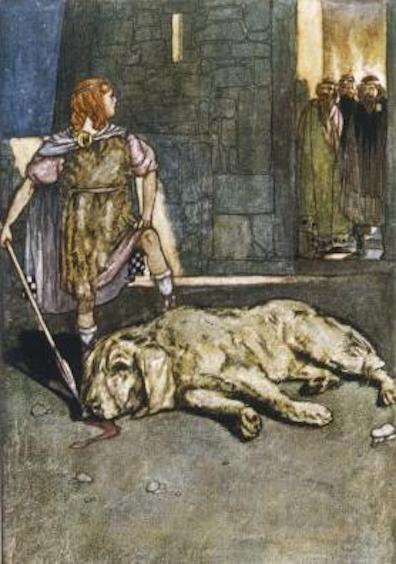

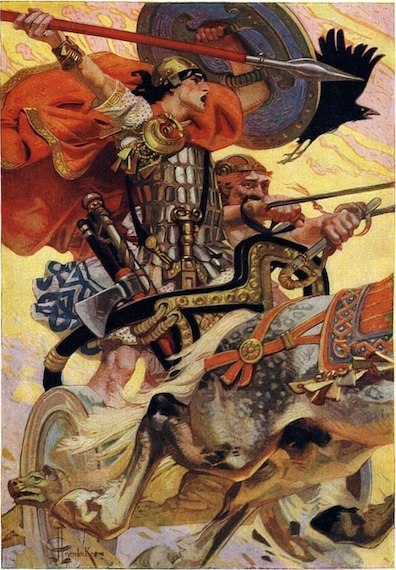

Cú Chulainn, the semidivine warrior of the Ulster Cycle, is the

archetypal ancient Irish hero. He was born Sétanta, but after

being attacked by the smith Culain's fierce guard dog and

killing it, he offered to take its place as a guard and became

the Cú (Hound) of Chulainn (or Chulain, Chulin, Culain, or

Culann.) Like Achilles in Greek mythology, he is an irresistibly

strong warrior who becomes possessed by frenzy in battle,

cutting bloody swaths through armies in his chariot and

defeating opponent after opponent in single combat.

Slote, Mamigonian, and Turner note that "Irish mythological

heroes are typically accompanied by dogs." They quote from

Standish O'Grady's

History of Ireland (1881): "The

heroic age of Ireland is, in fact, the age of the Hounds; and

surely no nobler and more touching type of the heroic temper

could be selected than this magnanimous brute. [...] The hounds

of the third century of our era, the age of the Fenian heroes,

are dogs—the comrades of the warriors" (187).

Thus the Citizen is accompanied by a large dog—"that bloody

mangy mongrel, Garryowen." The narrator says, "I'm told for a

fact he ate a good part of the breeches off a constabulary man

in Santry that came round one time with a blue paper about a

licence," and the end of

Cyclops shows Garryowen rushing

to rid the Citizen of another enemy. But the parody also recalls

the act that gave Cú Chulainn his name, when the hero

disciplines his dog "

from time to time by tranquilising blows

of a mighty cudgel rudely fashioned out of paleolithic stone."

Like Polyphemus he is enormous, measuring "several ells" across

the shoulders (the ell is an English linear measure of 45

inches, well more than a meter), with "rocklike mountainous

knees," nostrils large enough for birds to nest in, and eyes the

size of cauliflowers. "A powerful current of warm breath"

streams from his cavernlike mouth, and his heartbeat is as

seismic: "

the loud strong hale reverberations of his

formidable heart thundered rumblingly causing the ground, the

summit of the lofty tower and the still loftier walls of the

cave to vibrate and tremble." Here again there is an echo

of Cú Chulainn. Standish O'Grady writes that "like the

sound of a mighty drum his heart beats" (232).

Slote and his collaborators also cite inspirations in P. W.

Joyce's

Social History of Ancient Ireland (1913) for

details of the hero's clothing. One item of ancient Irish garb

was "A large cloak, generally without sleeves, varying in

length, but commonly covering the whole person from the

shoulders down.... sometimes it was a formless mantle down to

the knees; but more often it was a loose though shaped cloak

reaching to the ankles" (2.193-94). The hero of the parody has a

"

long unsleeved garment of recently flayed oxhide reaching to

the knees."

These cloaks were made from cloth, not leather, but Joyce

augments the air of primitive savagery by draping his hero in

"recently flayed oxhide," and augments the impression by giving

him "brogues of salted cowhide laced with the windpipe of the

same beast." He wears also "

a loose kilt," which P. W.

Joyce notes "must have been very much worn both by ecclesiastics

and laymen" (2.203), and "

trews of deerskin," also

mentioned in the history: "Leggings of cloth, or of thin soft

leather, were worn, probably as an accompaniment to the kilt"

(2.209). (According to the

OED, trews are "Close-fitting

trousers, or breeches combined with stockings, formerly worn by

Irishmen and Scottish Highlanders.")

The

Social History of Ancient Ireland observes that "A

girdle or belt (Ir.

criss) was commonly worn round the

waist, inside the outer loose mantle," and "The girdles of

chiefs and other high-class people were often elaborately

ornamented" (2.212). Joyce's hero has "

a girdle of plaited

straw and rushes"—the familiar Irish

súgán—and it

is hung with carved stone images of other heroes. He wears socks

"

dyed in lichen purple," an adaptation of the information

that "Purple cloaks, purple flowers, and purple colour in

general, are very often mentioned in Irish writings.... Purple

dyestuff was obtained from a species of lichen" (2.216-18).

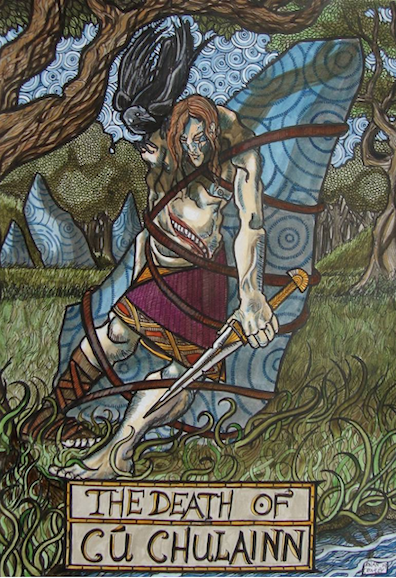

The superhuman figure of the parody, then, is indebted both to

scholarship on ancient Irish dress and popular mythological

accounts of ancient Irish warriors like Cú Chulainn—both of

which were required reading for enthusiasts of the Irish

Literary Revival. Joyce adds to them one final marker of

echt

ancient Irishness, the "

round tower" at whose base the

hero sits. Round towers were medieval stone buildings of a

distinctively Irish type. Usually built next to churches or

monasteries, they served as bell towers but also as defensive

fortifications in times of trouble. Nearly 20 of them remain in

good condition, out of perhaps 120 built throughout the country.

Seeking a heroic symbol of national identity for the Revival,

William Butler Yeats featured Cú Chulainn in five short plays

and some poems. Lady Gregory retold some of his legends in

Cuchulain

of Muirthemne (1902), toning down their

violence and making him the kind of hero children could

admire. But Joyce was uninterested in reviving Celtic

myths and unimpressed by muscular fighters, so he presents his

larger-than-life hero in a distinctly mock-heroic spirit. The

powerfully built Citizen can only be diminished by such greatly

exaggerated praises. By contrast, the puny newspaper vendor

Davy

Stephens used comedy to his advantage when he archly

modeled himself on an ancient hero:

His exterior is peculiar but prepossessing.

Standing a little below the usual height for the proverbial

Irishman, this point is quickly lost sight of in a deep well

of wit, not yet completely sounded, beaming forth in his eyes.

No one can say whether it is in the merry glance of his eye or

in the quick repartee that issues from his lips, never for a

moment sealed, that Davy’s fortune lies. The corners of his

mouth are turned up in a perpetual smile which his clean

shaven chin tends to emphasise. His hair hangs down over his

shoulders in long strings, reminding one of that of Ulysses

when tossed by the sea at the feet of the charming Nausicaa,

and the fresh breezes of the Channel have reduced his

complexion to a compromise between red and brown.... Add to

these particulars a fine rich brogue and the man is complete.