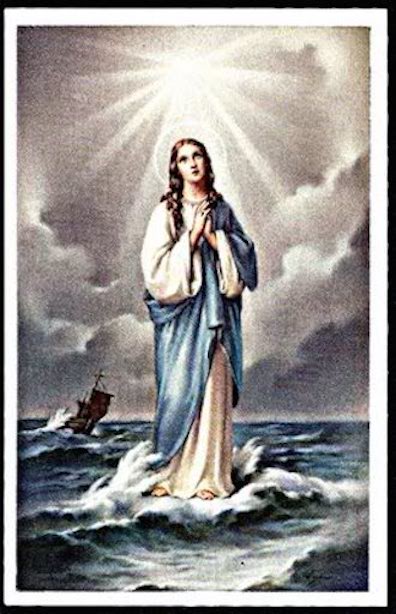

The name Star of the Sea (Latin Stella Maris) is one

of many Catholic titles for Jesus's mother: Our Lady, Mother

of God, Blessed Virgin, Queen of Heaven, Mystical Rose, Most

Pure, the New Eve. It may have been inspired partly by a

passage in Revelation: "And there appeared a great wonder in

heaven; a woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her

feet, and upon her head a crown of twelve stars" (12:1). After

obscure beginnings in the writings of Saint Jerome, Stella

Maris began to appear in ecclesiastical writings and

hymns of the 7th, 8th, and 9th centuries. At some point it

merged with seafarers' use of the same phrase for Polaris, the

unerring North Star of navigators. Sailors around the world

have long prayed to the Virgin Mary for deliverance from

storms, and many coastal churches around the world, like the one in Sandymount, have

been named Star of the Sea.

In Catholic devotions Mary is typically an intercessor

between sinners and God, and the nautical association has

inspired a metaphorical equivalent: the human heart is a

stormy sea and Mary a guiding light. In one of his 12th

century Marian homilies Saint Bernard of Clairvaux wrote, "If

the winds of temptation arise; if you are driven upon the

rocks of tribulation look to the star, call on Mary. If you

are tossed upon the waves of pride, of ambition, of envy, of

rivalry, look to the star, call on Mary. Should anger, or

avarice, or fleshly desire violently assail the frail vessel

of your soul, look at the star, call upon Mary." Joyce echoes

such language when the voices of men resisting alcoholic

temptation in the Sandymount church are said to pray "to her

who is in her pure radiance a beacon ever to the

stormtossed heart of man, Mary, star of the sea."

Marian devotions inevitably color sexual understandings of

women in Catholic countries. Joyce's Ireland was deeply

invested in the idea that unmarried women are either virgins

or whores. Stephen Dedalus's earliest glimmering of romantic

love, as a young boy in part 1 of A Portrait of the Artist

as a Young Man, comes in a Marian vision of the girl

next door: "Eileen had long thin cool white hands too because

she was a girl. They were like ivory; only soft. That was the

meaning of Tower of Ivory but protestants could not

understand it and made fun of it.... Her fair hair had

streamed out behind her like gold in the sun. Tower of

Ivory. House of Gold. By thinking of things you could

understand them." From this chastely spiritual beginning A

Portrait traces Stephen's descent into the dirty world

of sex workers, and back out. In part 5, as a university

student, he is still dreaming, albeit in what now seems a sexually charged way, of a woman

associated with "seraphim," "the smoke of praise," a

"eucharistic hymn," "sacrificing hands," and a "chalice."

Nausicaa takes this tension between sexual desire and

spiritual devotion to a new level of intensity, but now

thoughts of the Blessed Virgin inhabit the consciousness of a

young woman, herself as virginally naive as Stephen was before

visiting the Monto. Bloom's direction of carnal desire toward

this Virgin echoes in a most unorthodox way the worship taking

place in the church. One must note that Catholics strongly

object to the use of this word, "worship," in relation to

Mary: she is not a goddess, and so can receive only

"veneration" or "hyperdulia." They object in equal

measure to the word "mariolatry" (Mary + latria =

worship), a Protestant coinage that suggests idolatry. Joyce

did not hesitate to use either term, however. In a 3 January

1920 letter he described Nausicaa as "written in a

namby-pamby jammy marmalady drawersy (alto là!) style with

effects of incense, mariolatry, masturbation, stewed cockles,

painter's palette, chitchat, circumlocutions, etc., etc."

The incense and the painter's palette (in which shades of

blue predominate) hover around Gerty. Her hands are like

"finely veined alabaster" and her white face is "almost

spiritual in its ivorylike purity." Her eyes are "of the

bluest Irish blue," and in her carefully chosen palette of

sartorial colors blue is everywhere. She wears "A neat blouse

of electric blue" and a straw hat "trimmed with an underbrim

of eggblue chenille and at the side a butterfly bow to tone."

With four colors of undies to choose from, on this day she is

"wearing the blue for luck, hoping against hope, her own

colour and the lucky colour too for a bride to have a bit of

blue somewhere on her because the green she wore that day week

brought grief."

Thus iconographically defined as a Virgin, Gerty sits on the

seaside rocks listening to the men gathered "in that simple

fane beside the waves, after the storms of this weary

world, kneeling before the feet of the immaculate,

reciting the litany of Our Lady of Loreto, beseeching her to

intercede for them, the old familiar words, holy Mary, holy

virgin of virgins." From the church "the fragrant incense was

wafted and with it the fragrant names of her who was

conceived without stain of original sin, spiritual vessel,

pray for us, honourable vessel, pray for us, vessel of

singular devotion, pray for us, mystical rose. The

priest has told the men inside "what the great saint

Bernard said in his famous prayer of Mary, the most pious

Virgin's intercessory power that it was not recorded in

any age that those who implored her powerful protection were

ever abandoned by her." Gerty savors these devotional phrases

in memory, and she pictures the "scene in the church, the

stained glass windows lighted up, the candles, the flowers and

the blue banners of the blessed Virgin's sodality."

While she imagines these supplications to the Virgin in the

church, Bloom pays his devotions to the one nearest him. "His

dark eyes fixed themselves on her again drinking in her every

contour, literally worshipping at her shrine." Gerty

swings her legs in time to the hymns in the church and leans

far back, "and the garters were blue to match on account of

the transparent" and "he couldn't resist the sight of the

wondrous revealment half offered." Bloom's masturbation

makes him the storm-tossed supplicant, and Gerty plays her

corresponding role as the ever-tolerant, ever-indulgent Virgin

Mother and Mystical Rose. "Her woman's instinct told her that

she had raised the devil in him and at the thought a burning

scarlet swept from throat to brow till the lovely colour of

her face became a glorious rose." Although he has

profaned her sacred mystery, "there was an infinite store

of mercy in those eyes, for him too a word of pardon even

though he had erred and sinned and wandered. Should a

girl tell? No, a thousand times no. That was their secret,

only theirs."