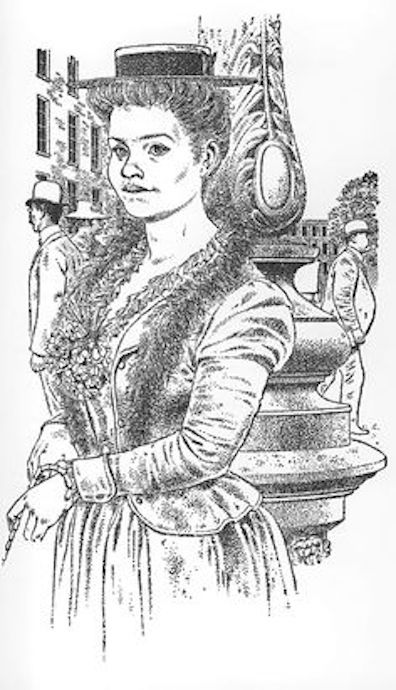

The woman Corley is seeing in "Two Gallants,"

as iilustrated by Robin Jacques. Source: James Joyce, Dubliners

(Grafton Books, 1977).

John

Corley

Yet one more character from Dubliners—perhaps the

most unlovely person in that gallery of human failures—enters

the pages of Ulysses when Stephen runs into "John

Corley" early in Eumaeus. In "Two Gallants," the

work-averse Corley, known only by his surname, is seen

un-gallantly preying on a servant girl, not so much for sex

(though he gets that) as for money. In Eumaeus he is

homeless, jobless, friendless, drunk, and still looking for

sources of easy money. But the novel also incorporates him in

a more dashing, successful guise. It is seldom remarked that

Corley gave Joyce a model for the similarly despicable Blazes

Boylan, whom Bloom calls "the worst man in Dublin."

Joyce said that the four stories in the second section of Dubliners

represent "adolescence." Their protagonists are not teenagers

but young men and women exploring life's possibilities,

finding work, contemplating marriage. "Two Gallants" opens

with two such men walking through town together. One of them

is doing all the talking, while the other obsequiously listens

and laughs, occasionally stepping into the street "owing to

his companion's rudeness." The speaker tells him of "a fine

tart" that he is seeing—a "slavey" who works in a house in

Baggot Street, a rich area on the southeast side of town. He

is having sex with this servant girl but has not told her his

name. Representing himself as temporarily unemployed but "a

bit of class," he has convinced her to pay the tram fares on

their dates and to bring him "Cigarettes every night," as well

as "two bloody fine cigars" clearly stolen from her employer.

These details mark the young woman as neither very bright nor

very honest, but painfully desperate for affection. "Maybe she

thinks you'll marry her," laughs Lenehan, who feigns moral

outrage ("Base betrayer!") while congratulating his companion

on a brilliant seduction ("You're what I call a gay

Lothario...And the proper kind of a Lothario, too!").

Corley’s stride acknowledged the compliment. The swing of his burly body made his friend execute a few light skips from the path to the roadway and back again. Corley was the son of an inspector of police and he had inherited his father’s frame and gait. He walked with his hands by his sides, holding himself erect and swaying his head from side to side. His head was large, globular and oily; it sweated in all weathers; and his large round hat, set upon it sideways, looked like a bulb which had grown out of another. He always stared straight before him as if he were on parade and, when he wished to gaze after someone in the street, it was necessary for him to move his body from the hips. At present he was about town. Whenever any job was vacant a friend was always ready to give him the hard word. He was often to be seen walking with policemen in plain clothes, talking earnestly. He knew the inner side of all affairs and was fond of delivering final judgments. He spoke without listening to the speech of his companions. His conversation was mainly about himself: what he had said to such a person and what such a person had said to him and what he had said to settle the matter. When he reported these dialogues he aspirated the first letter of his name after the manner of Florentines.

Wandering around out of work—"about town"—Corley listens to

friends who tell him about job openings, but such words are

"hard" for a man who evidently prefers to have money simply

handed to him. One source of income seems to be informing on

fellow citizens to the secret police, and here here the apple

has not fallen far from the tree. Eumaeus specifies

that he is not simply the son of an "inspector," but of "Inspector

Corley of the G division," notorious for its efforts to

root out republicanism.

Corley pronounces the letter "c" with a burst of throaty air

that makes it sound like "h," identifying him as a whore, and

the story proceeds to show him also making money from the

skillful marketing of his sexuality. Lenehan, jauntily dressed

but impecunious and widely regarded as a "leech," anxiously

asks more than once about an unspecified plan to get something

from the girl. Corley assures him, "I know the way to get

around her, man. She's a bit gone on me." He used to spend

money on girls, he confides, but "damn the thing I ever got

out of it—except with one woman, he admits "regretfully." She

was "a bit of all right" but is now "on the turf"—earning a

living as a prostitute—presumably after he ruined her

reputation and then dumped her.

Corley is walking to meet the new girl for a date. He won't

let Lenehan meet her, but agrees to let him observe her

unseen. She is in her "Sunday finery": a blue dress, a white

"sailor hat," a black leather belt with a great silver buckle,

a white blouse, and "a short black jacket with mother-of-pearl

buttons and a ragged black boa." Some red flowers are

"pinned in her bosom," and the air where she is standing is

"heavily scented." Lenehan approves of "her stout short

muscular body. Frank rude health glowed in her face, on her

fat red cheeks and in her unabashed blue eyes. Her features

were blunt. She had broad nostrils, a straggling mouth which

lay open in a contented leer, and two projecting front teeth."

Lenehan goes off to kill time, eat a miserably poor supper,

and dream of settling down with "some good simple-minded girl

with a little of the ready." At the end of the story, Corley

walks back down the street with his date and says goodbye to

her. To Lenehan, sick with fear that his plan has failed, he

opens a hand to reveal a gold

sovereign.

Not only does the pound coin suggest masculine rule, colonial

degradation, and meretricious simony, but it is a phenomenal

sum for such a poor girl to have given away—perhaps a quarter

of her annual salary, or even more. (The apparent theft

illustrates the thinking behind the "No followers" epression

of Dublin employment ads: girl wanted, no dangerous males in

tow.) History repeats itself when a well-oiled Corley begs

money from Stephen in Eumaeus, complaining that he has

"Not as much as a farthing to purchase a night's lodgings. His

friends had all deserted him. Furthermore he had a row with

Lenehan and called him to Stephen a mean bloody swab with a

sprinkling of a number of other uncalledfor expressions. He

was out of a job and implored of Stephen to tell him where on

God's earth he could get something, anything at all, to do."

Stephen tells him that in a day or two there will be an

opening for a teacher at Mr. Deasy's school in Dalkey, even

saying that "You may mention my name," but Corley begs off,

saying that school was never his strong suit. Stephen gives

him what he thinks is a penny but is actually a half crown,

worth thirty times as much. Financial windfalls continue to

visit this most unworthy man.

Little has changed from the time represented in "Two

Gallants" except that Corley is now destitute, shuffling along

dark deserted streets rather than strolling triumphantly down

Baggott Street with a girl on his arm. Some of his old

dashing manner enters the pages of Ulysses in a

different person, however. The Corley of Dubliners has

"something of the conqueror" in his manner, one aspect of

which is an air of not wanting a woman overmuch. He tells

Lenehan, "I always let her wait a bit." Blazes Boylan plays

the same role of a conquering Don Juan, attracting women with

his air of affluence and confident unconcern. In Sirens

he comes into the bar, orders a drink, and asks, "What time is

that?... Four?" The assignation with Molly is set for 4:00,

and Eccles Street is some distance away. Bloom thinks, "At

four. Has he forgotten? Perhaps a trick. Not come: whet

appetite. I couldn't do."

The surest sign that Joyce was thinking of Corley when he

penned Boylan is the fact that Lenehan has

transferred his sycophantishly leering attentions from the

one to the other.

He meets Boylan in the Ormond by prearrangement and hails him

in the language applied to Corley: "See the conquering hero

comes." They talk about betting on Sceptre in the Gold

Cup and Boylan brags about his latest sexual adventure:

"— I plunged a bit, said Boylan winking and drinking. Not

on my own, you know. Fancy of a friend of mine." Ithaca

and Penelope show that he has indeed placed a bet for

Molly. That detail is not Corley-like, to be sure, but the

leering complicity between Boylan and Lenehan absolutely

recalls "Two Gallants." In Circe Lenehan "officiously

detaches a long hair from Blazes Boylan’s coat shoulder"

and congratulates him on a successful seduction, which Boylan

complacently

likens to nabbing a hearty meal:

LENEHAN

Ho! What do I here behold? Were you brushing the cobwebs off a few quims?

BOYLAN

(Sated, smiles.) Plucking a turkey.

LENEHAN

A good night’s work.

BOYLAN

(Holding up four thick bluntungulated fingers, winks.) Blazes Kate! Up to sample or your money back. (He holds out a forefinger.) Smell that.

LENEHAN

(Smells gleefully.) Ah! Lobster and mayonnaise. Ah!

ZOE AND FLORRY

(Laugh together.) Ha ha ha ha.

Corley apparently had a real-life model, but the

correspondences are only partial. Vivien Igoe writes that

"Joyce knew a Michael Corley who lived on the North Circular

Road and met him on one of his trips to Dublin from Trieste

when Corley wanted to borrow money from him. He reported that

Corley was delighted to hear that he was in one of his

stories." (Hah!) Slote, Mamigonian, and Turner add that

"During his trip to Dublin in 1909, Joyce wrote to Stanislaus

that Corley asked for money every time he saw him (Letters,

vol. 2, p. 275)." This man, the only Michael Corley listed on

the 1901 and 1911 census rolls, was born in 1850 and worked as

a "commercial traveler." He died in a workhouse on 1 January

1916 and was buried in a pauper's grave in the Glasnevin

cemetery.

Much as Joyce assigned bits of his Dubliners

character to both John Corley and Blazes Boylan, it seems that

he split Michael Corley into two persons. Like Michael, John

Corley is a wandering mendicant heading for a bad end, but he

is much younger. The name Michael is given to a fictional

person better suited to the real man's age: the narrator of Eumaeus

identifies John Corley's grandfather as "Patrick Michael

Corley of New Ross."