Bloom is an Odysseus who has returned home to his Ithaca, and

at the end of his day the narrative says, "He rests. He has

travelled." It then poses a question: "With?" The

answer is Sinbad (or Sindbad), an 8th or 9th century Arabian

hero whose seven voyages unquestionably owe much to those of

Homer's hero. (The Odyssey was translated into Arabic

by the 8th century, and the story of Polyphemos is retold in

Sinbad's third voyage.) Sinbad thus joins Rip Van

Winkle, Enoch Arden, the Wandering Jew, and a small

host of fellow travelers who function as additional symbolic

analogues for Bloom's Odyssean mental adventures.

In Surface and Symbol, Robert Martin Adams observes

that along with "Sinbad the Sailor," "Tinbad"

and "Whinbad" were characters in the Sinbad pantomime

performed in Dublin in 1892 and 1893 (80). These names have

evidently prompted Bloom to transpose Sinbad's story into his

beloved register of nursery

rhyme, where silly verbal resemblances can drive a story

forward and people can become fancifully identified with their

occupations (Tinbad the Tailor, Jinbad the Jailer, Whinbad the

Whaler, Ninbad the Nailer, Binbad the Bailer, Pinbad the

Pailer, Minbad the Mailer, Hinbad the Hailer, Rinbad the

Railer). It is perhaps not too great a stretch to hear in

these phrases all the occupations that Bloom has encountered

people practicing in the course of his day, or remembered

himself practicing in earlier years, or imagined himself

practicing in a different life. (In Circe Bloom's

adventures of June 16 are cast as a similar-sounding series of

hagiographic attributes: "Kidney of Bloom, pray for us. /

Flower of the bath, pray for us. / Mentor of Menton, pray for

us. / Canvasser for the Freeman, pray for us....") As a kind

of Odysseus who has completed his long and eventful day's

journey and come at last to rest in his Ithacan bed, Bloom

sinks down into sleep "With" the similar figure of Sinbad,

spouting silly nursery rhymes all the way.

In the following paragraph, by asking itself the correlative

question "When?," the narrative continues the journey

motif by locating Bloom on a temporal slide into

unconsciousness: "Going to dark bed there was a square

round Sinbad the Sailor roc's auk's egg in the night of the

bed of all the auks of the rocs of Darkinbad the

Brightdayler." This sentence does not exactly answer the

question, but in a striking feat of mimetic representation the

bed into which Bloom is sinking becomes the site of a

bewildering host of associations, as if his mind is speeding

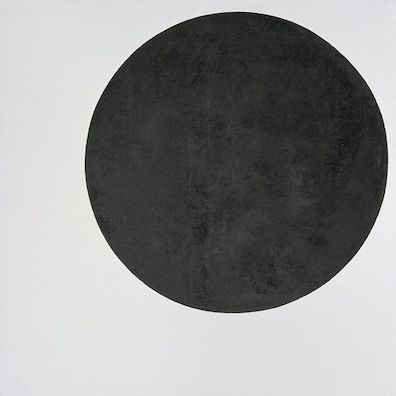

up rather than slowing down. The bed is dark, anticipating the

black extinction of consciousness expressed in the large black

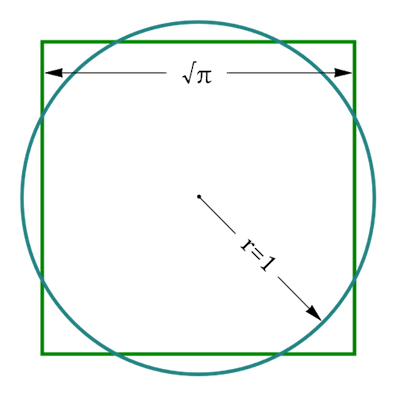

dot at the end of the chapter. And the egg is "square round,"

a paradoxical figure that evokes the mathematical challenge

referred to earlier in Ithaca as "the quadrature of the

circle."

Why should Bloom be thinking such a thought at this moment?

Gifford hears an allusion to the end of Dante's Paradiso,

where the idea of squaring the circle conveys the pilgrim's

inability to rationally fathom the mystery of the

Incarnation—a failure that immediately precedes his mystical

vision of God. Although other annotators (including the

normally very thorough Slote) decline to second Gifford's

suggestion, it makes excellent sense given the temporal

context of Bloom "Going to dark bed" and approaching the

extinction of consciousness. Dante uses the famous

mathematical challenge to characterize his last moment of

ordinary human consciousness before he experiences the flash

of mystical enlightenment. Staring into the divine abyss, he

describes his struggle to understand its mysterious union with

humanity in the person of Christ:

Like the geometer who fully applies himself

to square the circle and, for all his thought,

cannot discover the principle he lacks,

such was I at that strange new sight.

I tried to see how the image fit the circle

and how it found its where in it.

(33.133-37)

Dante writes that he struggled to comprehend the mystery of

the incarnate godhead (the circle's constitutive principle of

π has now been shown to be just such a transcendental entity)

and that he would have failed "had not my mind been struck by

a bolt / of lightning that granted what I asked" (141-42).

After his mind's fruitless efforts at logical comprehension, a

mystical vision sweeps him up into the Love moving the sun and

the other stars and concludes the epic poem. If this allusion

lurks within Bloom's phrase "square round," it serves to

characterize Bloom's coming entry into the realm of sleep and

dream, which waking intelligence cannot comprehend. And here

Joyce's text alludes a second time to the Paradiso, in

a detail which Gifford did not notice but which provides

powerful confirmation of his hypothesis. Trying to fathom how

the image of mankind inheres in the divine circles above him,

Dante's pilgrim asks "come vi s'indova"—literally,

in a kind of neologism that Dante employs throughout the

Paradiso, "how it in-whered itself in it." Ithaca ends with

the question, "Where?" The answer is the large black

dot of incipient sleep.

The

square round roc's auk's egg carries still more

associations.

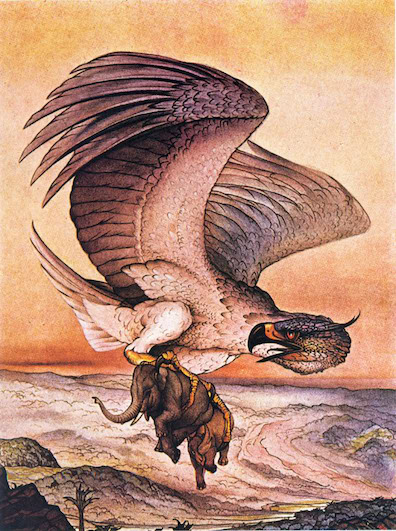

In the Sinbad stories, the roc is an enormous raptor, powerful

enough to carry elephants and huge snakes to its nest to feed

its young. In his second voyage Sinbad hitches a ride on a roc

to the valley of diamonds,

and then he tricks one into carrying him back to its nest. On

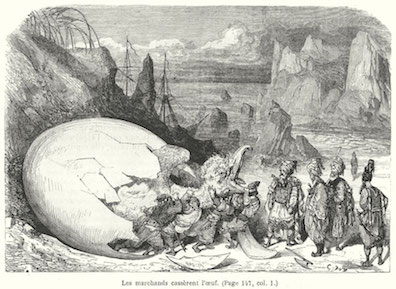

another voyage, the fifth, his crew spots an immense roc's

egg, breaks it open, and eats the chick, bringing

destruction down upon themselves from the avian parents much

as Homer's men do when they kill the cattle of the sun god.

Joyce may still be injecting echoes of the Commedia

into Bloom's thoughts here: Dante's pilgrim gets his first

taste of mystical rapture in canto 9 of Purgatorio

when, in a dream, an eagle carries him Ganymede-like into the

sphere of fire, filling him with terror. But the roc also has

powerful associations with Sinbad's great topic, the

acquisition of wealth. (He tells his tales to a poor man, also

named Sinbad, who wants to know why some people enjoy great

riches while others must endure poverty.) Getting to the

valley of diamonds by roc, and thence to a roc's nest, has

enriched the hero with a trove of gems.

Bloom's preoccupation with accumulating wealth ensures not

only that this part of the Sinbad story would appeal to him,

but also that he would think of it at bedtime. Earlier in

Ithaca, he has contemplated various fantastic schemes for

getting rich, one of them involving finding "an antique

dynastical ring" that has been "dropped by an eagle in

flight." The narrative asks why Bloom should spend time

dreaming up such outlandish ideas, and answers that he has

learned from experience that happily fantasizing about wealth

before going to bed helps him to sleep well. At the end of the

chapter, then, as he drifts off to sleep, the pantomime's

story of a raptor associated with great wealth predictably

enters his thoughts. Given Joyce's incredible capacity for

layering multiple associations on top of one another within a

small detail, it seems possible that he added his own thoughts

of an eagle carrying a dreamer up to heaven with his

protagonist's thoughts of an eagle dropping wealth into his

lap.

All of these speculations about Bloom's thought processes in

his last moments of consciousness are inferential, and the

chains of association become more tenuous as the final

sentence of Ithaca reels toward the final incoherence

of the black dot. Why does the roc become an "auk," a

group of diving Atlantic sea-birds in the alcid family?

Certainly not because of size: even the extinct (ca. 1852)

great auk stood no higher than about 3 feet (1 meter). The

link is probably purely linguistic, one "oc" sound childishly

engendering another as in the nursery-rhyme variations on

Sinbad's name.

As

for "Darkinbad

the Brightdayler," this

is a hill that few of Joyce's annotators or commentators

have been willing to die on. Thornton, Gifford, Johnson,

Kiberd, and Slote all pass over it in dumb silence, and it

does not seem to have received very much attention in the

critical literature either. Adams supposes, not very

helplfully, there may be a "subtle reference to Max

Müller's theory that Odysseus was originally a sun-god" (Surface and Symbol, 81). It

seems to me more likely that Joyce here is continuing his

series of alliterative Sinbad the Sailor names. Sinbad

becomes Darkinbad because he has gone into a dark bed, and

Sailor perhaps becomes Brightdayler because this place of

dark night opens, on the other side of unconsciousness,

onto the bright daylight of dreams. Probably other

meanings can be detected in the two words. As in

experiences of Finnegans Wake, Joyce

points his readers toward some well-defined ambiguities

and encourages them to add their own.

To

his credit, Adams observes that at some point all efforts

of critical interpretation should be abandoned

because "the going-to-bed litany is a piece of inspired

stupidity, like Charles Bovary's famous hat, containing layer

after layer of meaninglessness—an unfathomable depth of mental

void. Relaxing its hold on external reality, and on its own

thought processes, the mind is shown drifting off into a

mechanical word-cuddling, and so into complete darkness. The

more we project conscious intellectual meaning into the

process, the less it serves its overt purpose. Like a

Rorschach-blot, the passage will absorb anything we want to

put into it, but there is a point at which our insertions, by

expressing 'us' all too richly, frustrate the ends of the

novel" (82).

This caveat serves a valuable purpose. Bloom's muddy

half-thoughts are certainly more than a little stupid, as are

those of every human being drifting off to sleep. But readers

can also benefit from the hindsight of knowing something of

the book that Joyce wrote next. Finnegans Wake, the

ultimate Rorschach blot, suggests that in sleep thousands of

suggestive threads of meaning become tied together in patterns

that do not respect the laws of daylight logic but are easily

as complex as waking thoughts. The

accelerating flood of half-coherent ideations represented

at the end of Ithaca evokes

this daily human passage from the crowded reality of

daytime thoughts to the less comprehensible but still more

crowded experience of dreams. Could Joyce already have

been thinking of his book of Darkinbad as he finished his

book of Bright Day? A note full of credulity-straining

suppositions will conclude with one more: amid the list of

Sinbad's alliterative cousins is one, "Finbad the Failer," whose

name richly evokes the next defeated conqueror on Joyce's

horizon.