At the beginning of Ithaca the conversation between

Stephen and Bloom appears to be going much better than it did

in most of Eumaeus, but at least one of Stephen's

ideas clearly strikes Bloom as, in the words of Eumaeus,

"a bit out of his sublunary depth." He declines to voice an

opinion on what his young companion calls "the eternal

affirmation of the spirit of man in literature," a phrase

which strongly recalls ideas that the young Joyce had

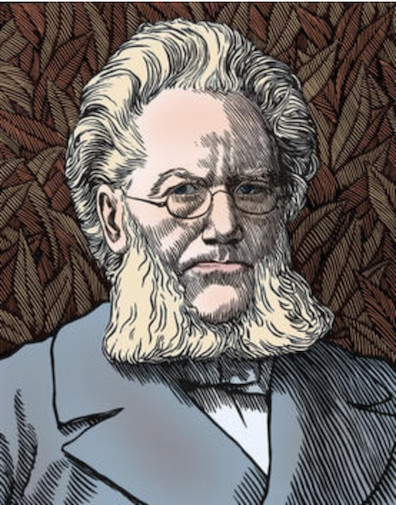

advocated in a lecture inspired by Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen. The lecture

praised art which affirms human life but tells the truth about

it, no matter how unflattering.

In January 1900, when he was only seventeen years old, Joyce

delivered a lecture titled "Drama and Life" to the Literary

and Historical Society of University College, Dublin. In this

important announcement of aesthetic views that would continue,

with some significant modifications, to occupy Joyce

throughout his writing career, he argued that great drama was

superior not only to facile stagecraft but also to mere

"literature" for its capacity to represent enduring truths of

human experience. Later, persuaded in part by his own greater

talent for novelistic fiction than for stage plays, Joyce

abandoned the invidious distinction between drama and

literature. But he maintained his belief that fiction should

represent eternal truths of the human condition.

"Drama and Life" proposes that "Human society is the

embodiment of changeless laws which the whimsicalities

and circumstances of men and women involve and overwrap." The

essay presents these "eternal conditions"

metaphorically as the "spirit" of humankind: "It might be said

fantastically that as soon as men and women began life in the

world there was above them and about them, a spirit,

of which they were dimly conscious, which they would have had

sojourn in their midst in deeper intimacy and for whose truth

they became seekers in after times, longing to lay hands upon

it. For this spirit is as the roaming air, little susceptible

of change, and never left their vision, shall never leave

it, till the firmament is as a scroll rolled away."

The artist who seeks to capture this eternal spirit in words

studies "men and women as we meet them in the real world, not

as we apprehend them in the world of faery." Such pitiless

scrutiny is a stronger response to life, Joyce argued, than

high-minded idealization of the human condition, or earnest

ethical programs, or religious worship, or pursuit of beauty,

or mere amusement. Such an art "may help us to make our

resting places with a greater insight and a greater foresight"

because it grounds us in the unpretty, but substantial, truth

of what we are. The powerful "Yes"

with which Molly concludes Ulysses breathes the same

spirit of looking hard at what life has offered and affirming

its value.

[2025] Slote, Mamigonian, and Turner cite another of Joyce's

early essays which contains an even more exact anticipation of

Ithaca's mention of "the eternal affirmation

of the spirit of man in literature." In the 1902 essay

on James Clarence Mangan Joyce wrote: "all those who have

written nobly have not written in vain, though the desperate

and weary have never heard the silver laughter of wisdom. Nay,

shall not such as these have part, because of that high,

original purpose which remembering painfully or by way of

prophecy they would make clear, in the continual

affirmation of the spirit?" The commentators note that

Joyce returned to this formulation in Stephen Hero:

"The age, though it bury itself fathoms deep in formulas and

machinery, has need of these realities, which alone give and

sustain life.... Thus the spirit of man makes a continual

affirmation."