"Inisfail the fair" quotes from the first line of Prince

Alfrid's Itinerary through Ireland, Mangan's 15-quatrain

translation of an old poem in Irish:

I found in Innisfail the fair,

In Ireland, while in exile there,

Women of worth, both grave and gay men,

Many clerics and many laymen.

I traveled its fruitful provinces round,

And in every one of the five I found,

Alike in church and in palace hall,

Abudant apparel and food for all.

Gold and silver I found in money;

Plenty of wheat and plenty of honey;

I found God's people rich in pity,

Found many a feast, and many a city....

Alfrid was a prince, and later King, of the Saxons in

Northumbria. In his

Life of St. Cuthbert, Bede mentions

his having been educated in Ireland ca. 684 AD. Alfrid's

educational accomplishments evidently included facility in the

Irish language, which he employed in writing this poem. The word

inis means "island," and the

Fál or

Lia Fáil

was the Stone of Destiny on the Hill of Tara in County Meath,

where all the early kings of Ireland were said to have been

crowned.

Inisfail is thus the Island of Destiny, a name

that carries with it thoughts of a bygone heroic age.

Alfrid sings the praises of the men and women of Ireland's

various provinces: "Armagh the splendid," Munster, Connaught,

Connall [Donegal], Ulster, Boyle, "Leinster the smooth and

sleek, / From Dublin to Slewmargy's peak," Ossorie, Meath.

Joyce's parody closely follows the language of the poem when

it says that "Lovely maidens" inhabit Erin's landscapes, "And

heroes voyage from afar to woo them, from Eblana [Dublin

before Dublin existed] to Slievemargy, the peerless

princes of unfettered Munster and of Connacht the just and

of smooth sleek Leinster and of Cruahan's land and of Armagh

the splendid and of the noble district of Boyle, princes,

the sons of kings."

The heroizing continues in the following sentence when H.

O'Connell Fitzsimon (listed in the 1904 Thom's

directory as superintendent of the food market) is seen

inventorying "herds and fatlings and firstfruits of that

land": "for O'Connell Fitzsimon takes toll of them, a

chieftain descended from chieftains." The spirit of

surveying Ireland's regions returns at the end of the parody's

third paragraph: "pasturelands of Lusk and Rush and

Carrickmines and from the streamy vales of Thomond, from the

M'Gillicuddy's reeks the inaccessible and lordly Shannon the

unfathomable, and from the gentle declivities of the place of

the race of Kiar."

These mentions of places and people impart an air of epic

(and archaic) Irish greatness to the parody, and its epic

catalogues of foodstuffs may likewise have been conceived as a

response to the many mentions of food in Alfrid's poem. But on

the subject of natural bounty Joyce found his own notes to

sing. His seemingly endless enumerations of fishes, trees,

vegetables, fruits, and animals announce a new technique in Ulysses:

prodigious lists reminiscent of biblical begats or Homeric

ships. The lists continue in many other parodies in Cyclops,

and they also figure prominently in Circe and Ithaca.

Catalogues like these are an ancient literary device, but

Joyce added to them his own distinctive notes of wild mockery.

In large part his parodic description of the markets sounds

like a reprise of the grandioloquent speech

about Ireland's natural wonders read aloud by Ned Lambert in Aeolus.

Dan Dawson's purple prose—e.g., "bosky grove and undulating

plain and luscious pastureland of vernal green, steeped in

the transcendent translucent glow of our mild mysterious

Irish twilight"—expresses a proud Hibernophilia that was

much in vogue at the turn of the last century, feeding the

enthusiasm for Celtic Twilight imagery in literature and

promoting postcolonial visions of agricultural independence

among activists. But Joyce holds it up to mockery, having the

men in the newspaper office rail on "the inflated windbag!"

Rather than relying on outside commentary, the Cyclops

parody mocks itself from within. After listing ten kinds of

fish that swim in Irish waters, the prose oafishly invokes

infinity: "the mixed coarse fish generally and other denizens

of the aqueous kingdom too numerous to be enumerated."

Artificial treatments of nature render nature artificial:

"other ornaments of the arboreal world with which that region

is thoroughly well supplied." Dawson's love of unnecessary

adjectives devolves into complete absurdity: "the lofty trees

wave in different directions their firstclass foliage."

Adjectives that don't do much in the first instance are

ineptly repeated: "Lovely maidens sit in close proximity to

the roots of the lovely trees singing the most lovely songs

while they play with all kinds of lovely objects." Verbosity

begets tautology: "mariners who traverse the extensive sea in

barks built expressly for that purpose." Hyperbole produces

bathos: "highly distinguished swine." Exceptionalism becomes

ridiculous: "oblong eggs."

As with all instances of Joycean mockery, however, it is

worth considering the possibility of some jocoserious

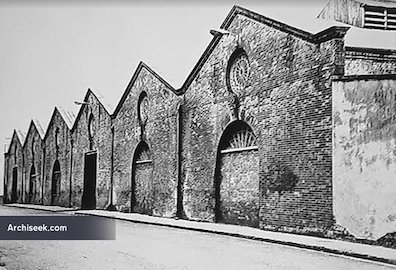

intent. The large Victorian structure called the Fruit and

Vegetable Market, which opened for business in December 1892,

was a source of great civic pride. It replaced an assortment

of dirty street stalls with one architectually magnificent and

hygienically conceived market. The Fish Market next door, also

built in 1892 and opened a few years later, was less

architecturally interesting but no less grand in scale. Slote,

Mamigonian, and Turner observe that the word "crystal"

that Joyce attaches to the produce market's glass roof might

have been meant to evoke the famous iron and glass Crystal

Palace that was built for the Great Exhibition in London in

1851. Sited in a very run-down, squalid part of north-central

Dublin, the new markets represented a hopeful kind of urban

transformation. One may perhaps hear in Joyce's overblown

lists of Irish natural bounty some quiet appreciation for

heroic civic accomplishment.