Etheric

double

Parody. "In the darkness spirit hands were felt to

flutter.... Assurances were given that the matter would be

attended to and it was intimated that this had given

satisfaction": in the seventh Cyclops interruption

Joyce turns his focus to a different enthusiasm of the

Irish Revival era, Theosophy. Joe Hynes's news of Paddy

Dignam's death prompts a news flash from the spirit world

about how he's doing out there. The beliefs echoed in this

passage are so outlandish as to defy parodic exaggeration, so

Joyce presents them more or less faithfully, but with no less

mockery than he gave Cuchulainn. The passage's air of

reverently contemplating spiritual truths is subverted by

persistent earthly concerns: Dignam has been liberated from

his physical body, but he remains hilariously fixated on

corporeal pleasures, modern housing conveniences, the dirt

piled on his coffin, a lost shoe.

One belief in particular is central to the Cyclops parody. The "etheric double," according to the doctrine, is the first in a series of progressively finer replicas of the human body known collectively as a person's aura or astral body, which is not an emanation from the physical body so much as an essential form that predates, generates, and sustains it. At the moment of death, this "double" stands outside the physical body and perceives realities normally unavailable to physical sight, but not in the permanent way that eternal truths are revealed to Christian souls. The double hovers near the physical corpse and, as Gifford puts it, "it gradually disintegrates; subsequently a new etheric body will be created for the rebirth of the soul, since one earth-life is not considered sufficient for the full evolution of the soul. In context, Dignam's etheric double is 'particularly lifelike' because it is only just beginning to disintegrate."

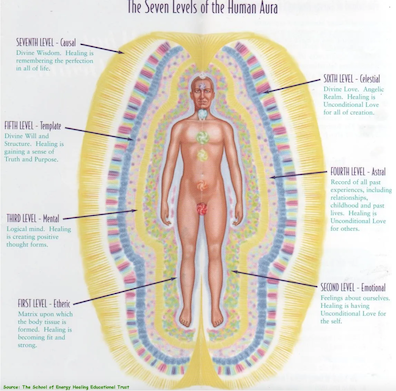

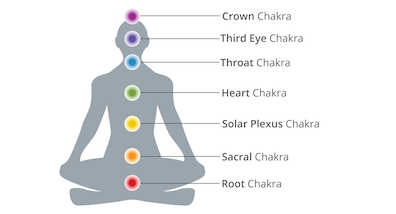

The sense organs of the etheric body are the Hindu chakras (Sanskrit for wheel) which impart vitality to the physical body and also effect communication between the earthly and astral planes. Joyce's parody describes a spiritualist séance in which the living make contact with the departed Dignam via these energy centers: "when prayer by tantras had been directed to the proper quarter a faint but increasing luminosity of ruby light became gradually visible, the apparition of the etheric double being particularly lifelike owing to the discharge of jivic rays from the crown of the head and face. Communication was effected through the pituitary body and also by means of the orangefiery and scarlet rays emanating from the sacral region and solar plexus." These sentences faithfully reproduce a number of Theosophical teachings about the chakras.

Hindu tantras are ritual formulas for effecting magical change, both "white" and "black" according to Blavatsky. Here, the chanting of tantras causes Dignam's luminous aura to appear, its "jivic rays" reflecting Hindu teachings about the jiva, a universal life-principle manifested on the seven planes of existence—Blavatsky calls it "a ray, a breath of the ABSOLUTE." Dignam's rays emanate from "the crown of the head" (the seventh, highest chakra) and from the "face" (the sixth). The sixth chakra, which is located between the eyebrows and associated with the pituitary and pineal glands, is the "third eye" that enables spiritual vision. Leadbeater writes in The Chakras (1927) that for some people "the pituitary body" constitutes "practically the only direct link between the physical and the higher planes." The "sacral region" and "solar plexus" are the second and third chakras, located respectively several inches below and above the navel. Joyce thus mentions four of the seven chakras. His luminous colors reflect Theosophists' assignment of different colors and symbolic meanings to the various chakras.

In addition to sketching the contours of the non-physical body, the parody introduces Theosophical eschatology when Paddy is "Questioned by his earthname as to his whereabouts in the heavenworld." Blavatsky called the state between death and reincarnation the Devachan—"heaven-world" or "place of the gods" (Deva, a word referenced later in the parody, means shining one, god, heavenly being). Paddy replies that "he was now on the path of prālāyā or return"—not a Christian return to the Creator but reincarnation in a new life. The Hindu term pralaya (destruction, dissolution, rest) refers to a period of nonexistence between manifestations—typically the end of the universe between cosmic cycles, but here the time in which the individual has died and not yet returned to physical existence.

During this hiatus between existential manifestations the spirit hangs in a liminal state, aspiring to higher spiritual conditions but still tethered to earthly attachments and tormented by unsatisfied desires. Paddy says that he is undergoing "trial at the hands of certain bloodthirsty entities on the lower astral levels." I do not know of a source for this idea, but he may be referring to the demonic spirits found in some Indian subcontinent religions, to the restless ghosts of people who died violently, or to vicious forces within the individual psyche. He reports, however, "that those who had passed over had summit possibilities of atmic development opened up to them." Atma or Atman is the divine principle within or behind each individual self that is imperishable and unaffected by worldly experience. Some highly evolved spirits achieve liberation from the endless cycle of births and deaths, and realize the Atman within themselves. This is the "summit" of human aspiration.

Maya (appearance, illusion, magic) is the Sanskrit word for the illusory nature of all cosmic manifestations, all phenomena. In The Key to Theosophy Blavatsky writes that "everything is illusion (Maya) outside of eternal truth, which has neither form, colour, nor limitation. He who has placed himself beyond the veil of maya—and such are the highest Adepts and Initiates—can have no Devachan." People who have reached the summit of atmic development, in other words, transcend the liminal state, but "The Devachanee lives its intermediate cycle between two incarnations." Paddy is not one of the Adepts, but he takes advantage of his present devanic detachment to warn people living in the grip of illusion that they should change their lives. "Asked if he had any message for the living," he "exhorted all who were still at the wrong side of Māyā to acknowledge the true path for it was reported in devanic circles that Mars and Jupiter were out for mischief on the eastern angle where the ram has power."

Joyce cannot be accused of exaggerating or falsifying these exotic doctrines, but he presents them in the irreverent spirit of all the parodies. In one small act of disrespect, he undermines the precise eastern truths by casually adding familiar English expressions to the mix. Dignam's questioners ask him about his "first sensations in the great divide beyond" and he says that "previously he had seen as in a glass darkly"—two western commonplaces in thinking about death, the latter from Paul's Corinthians. Far more subversively, he then mocks the notion of a liminal "devanic" state between earthly lives by showing the astral Dignam to be fundamentally no different from Paddy in the flesh.

"Interrogated as to whether life there resembled our experience in the flesh," Paddy reports that "more favoured beings now in the spirit"—more highly evolved souls, presumably, hovering on higher astral levels—tell him that "their abodes were equipped with every modern home comfort such as tālāfānā, ālāvātār, hātākāldā, wātāklāsāt." Life there, it seems, does resemble our experience in the flesh, and it may even (in the manner of crude Christian fantasies of heaven) improve it, with telephones and elevators for everyone. Rewarding spiritual purity with consumer conveniences surely violates the notion of seeing through the illusory goods of Maya. The mockery goes ballistic with the endless a's, not to mention the Sanskrit diacritical marks that Joyce added to them on page proofs of the first edition. They invite readers to adopt the reverent tone of a wise Indian sage while contemplating the virtues of hot and cold running water.

Earthly values persist, more subtly, in the news that "the highest adepts were steeped in waves of volupcy of the very purest nature." Volupty means pleasure, according to the OED, and the adjective "voluptuous" strongly connotes sexual pleasure. Being steeped in waves of it makes the pleasure sound distinctly orgasmic, as if Adepts are rewarded with something like the seventy virgins of Islam. Such a suggestion hardly suits the ascetic ethos of Theosophy, which expects sexual chastity, vegetarianism, and other kinds of corporeal discipline from its practitioners. Gifford tries to sidestep the implication by noting that the volupcy is pure, but nothing about "waves of volupcy" sounds very Theosophical. One might suppose that Joyce wanted to liken the experience of enlightenment to Christian notions of visionary ecstasy. But it seems more likely that he was sarcastically evoking a bordello.

As for Paddy himself, he seems not merely swayed by memories of his past life but still in it. Absurdly, he retains hunger and the ability to satisfy it: "Having requested a quart of buttermilk this was brought and evidently afforded relief." Asked "whether there were any special desires on the part of the defunct," he responds, "Mind C. K. doesn't pile it on." Theosophists of Joyce's era addressed each other with initials (in Scylla and Charybdis Blavatsky is "our very illustrious sister H.P.B."), and with this mode of address Paddy asks Corny Kelleher not to pile the dirt too heavily on his coffin. Certain aspects of earthly consciousness, it seems, are slow to disintegrate. This impression is hilariously amplified when Dignam tells his son where to find his missing boot and where to get it resoled, remarking that "this had greatly perturbed his peace of mind in the other region."

At least one more detail in this parody bears glossing. The people channeling Dignam's spirit hear, "We greet you, friends of earth, who are still in the body." The editors of JJON have found works indicating that both phrases, "friends of earth" and "still in the body," were current in Theosophical discourse of the 1880s and 90s.

The logo of the Theosophical movement, devised in 1875.

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The Etheric Double by A. E. Powell (1925). Source:

www.biblio.com.

The seven dimensions of the human aura. Source: medium.com.

The seven chakras. Source: www.google.com.

Undated photograph of Helena Petrovska Blavatsky. Source:

Wikimedia Commons.