Some phrases present the horse as very much a fleshly animal:

"a fourwalker, a hipshaker, a blackbuttocker, a taildangler, a

headhanger," "a good poor brute," "a big nervous foolish

noodly kind of a horse." But some odd word choices also seem

to remove this recognizable animal entirely from what Stephen

in Scylla and Charybdis calls "the whatness of

allhorse." The first is Bloom's admonition to Stephen, "Our

lives are in peril tonight. Beware of the steamroller."

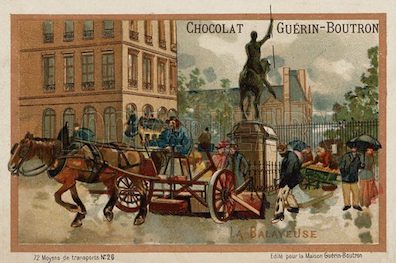

Some of the street-sweeping machines of this time did carry

large bristled rollers, and perhaps some of them had steam

engines, but there is nothing remotely steam-powered about

this one. Probably Bloom's warning emphasizes the size and

power of the apparition he comes upon in the dark, unable to

quite make it out (steamrollers were invented in the 1860s).

But the fanciful comparison distinctly overstates the case and

injects a mechanical element of steam-power that his senses

could hardly be registering.

Two sentences later Bloom gets a good look at the animal

"quite near so that it seemed new, a different grouping

of bones and even flesh." Again, the characterization

seems excessive. Bloom may be seeing the horse in a new way,

or even seeing clearly for the first time that it is a horse,

but that freshness of perception would hardly make it

new. Indeed, as a "headhanger" it seems old and tired. But

later in the same paragraph, Bloom's thoughts do provide a

context for seeing the animal as a different grouping of bones

and flesh: "But even a dog, he reflected, take that mongrel in

Barney Kiernan's, of the same size, would be a holy horror

to face. But it was no animal's fault in particular if he

was built that way like the camel, ship of the desert,

distilling grapes into potheen in his hump."

So a principle of metamorphosis is at work. Struck by the

great size of the animal looming up in the dark, Bloom

imagines it as being somewhat like a towering camel. But the

phrase "ship of the desert" complicates this picture. It is a

cliché, certainly, in a chapter chockablock full of clichés,

and Bloom's repetition of the tired commonplace might be

dismissed as simply a reflexive mental action. In the context

of fantastic substitutions, however, it threatens to take the

morphing horse out of the animal kingdom altogether. And, sure

enough, three sentences later the narrative voice of the

chapter affirms Bloom's inconvenient

comparison-within-a-comparison: "These timely reflections

anent the brutes of the field occupied his mind somewhat

distracted from Stephen's words while the ship of the

street was manoeuvring and Stephen went on about the

highly interesting old..."

Not only has the horse now been narratively authorized as a

ship, but it is "manoeuvring" through the avenue, like troops

on campaign or warships in formation. Individual sentient

beings are sometimes said to perform such an action ("She had

mastered the delicate maneuver"), but one would hardly expect

a poor horse to do so outside of the dressage ring. Looking

back to a sentence just before the remark about the

steamroller, one can see that this is not the first

inappropriate verb that has been applied to the horse: "By the

chains the horse slowly swerved to turn." Has anyone

ever seen a horse swerve? The word is usually applied to

vehicles, and in this case the vehicle would seem to be large

and unwieldy, like a Boeing 747 initiating a turn—or like an

immense passenger liner trying to avoid an iceberg.

In an unpublished paper presented to the summer 2019 Trieste

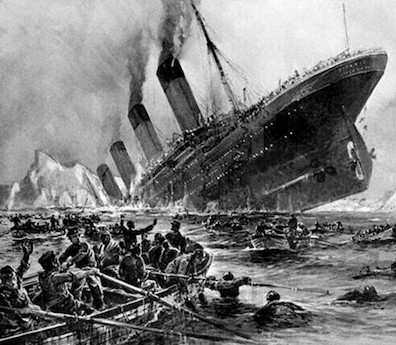

Joyce School, Senan Molony argues that echoes of the 1912

sinking of the Titanic pervade Eumaeus, and

that many of those echoes sound in this passage. Titanic

was "steam"-powered, and it plowed through ocean "rollers." It

was brand, spanking "new," celebrating its maiden voyage from

the U.K. to the U.S., and that passage proved to be a "holy

horror." The ship was named for the horrible giants that

assaulted the holy citadel of the Greek gods, and the iceberg

with which it crossed paths caused unfathomable horror by

ripping gaping holes in six of its watertight compartments.

(The vessel was designed to withstand rupture of three.)

Two more details catch Molony's attention: "The horse having

reached the end of his tether, so to speak, halted and,

rearing high a proud feathering tail, added his quota by

letting fall on the floor, which the brush would soon brush up

and polish, three smoking globes of turds. Slowly three times,

one after another, from a full crupper, he mired." If the

horse somehow predicts the Titanic, then its turds are

the ship's lifeboats, dropping away from the doomed vessel.

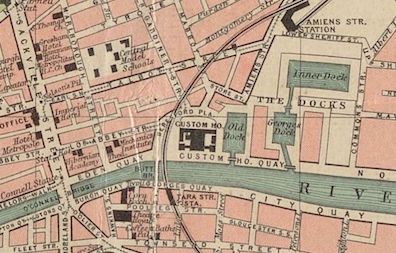

The second, closely related, detail is the location of the

ship's sinking: "Beresford Place," at the rear of the

Custom House. In addition to the man for whom this broad

avenue was actually named—John Beresford, a Wide Streets

Commissioner—Molony detects allusions to several individuals

relevant to the actions being described: "In 1887 an Admiral

Charles Beresford chaired a House of Commons Select

Committee on Saving Life at Sea. His committee recommended

'that all sea-going passenger ships should be compelled by law

to carry such boats, and other life-saving apparatus, as would

in the aggregate best provide for the safety of all on board

in moderate weather.' A quarter of a century later, in 1912,

the same Admiral Lord Beresford, now an MP, is back, and being

widely quoted about lifeboat provision on board the Titanic."

Another Beresford was involved in the same battle of

regulatory oversight: in 1872, "a Francis Beresford MP

tabled an amendment to legislation proposing that

'certificates should not be granted to passenger ships unless

they are provided with lifeboats and deck rafts sufficient to

save all on board in case of disaster or shipwreck.'"

Neither of these men is explicitly named in Ulysses,

so perhaps their connection with the scandalously inadequate

number of lifeboats aboard the Titanic can be

dismissed as coincidence. But yet another Beresford does make

an appearance in Cyclops: "Sir John Beresford,

of earlier date, a Royal Navy disciplinarian who is

denounced by the Citizen for giving miscreant sailors the

lash. Remarkably, his middle name is ‘Poo.’ Sir John Poo

Beresford. And here’s a horse doing a poo in Beresford Place…"

Why, one may ask, would Joyce have attached an individual's

name to the savage discipline of the British navy if he had

not been planning to make something of that name in a later

chapter?

If Molony's reading of all these strange details is not too

ingenious (and no one who studies the works of James Joyce

should be too quick to level that charge!), then one

wonders not only at the deliberate anachronism of Joyce's

symbolism, but also at how he compares the lowering of the Titanic's

lifeboats to the defecations of a horse. The first puzzle may

perhaps be resolved by invoking an ambitious device of

literary realism that Joyce borrowed

from Dante. The second perhaps lends itself to cruder

analysis. Noting that the stunning wreck of the great vessel

provoked heated public debate among Joseph Conrad, Arthur

Conan Doyle, and George Bernard Shaw, Molony sees subversive

scatalogical humor at play. "In making poo of the great iconic

event of April 1912," he speculates, Joyce comments on these

"high-profile literary spats on the cause and meaning of

the Titanic disaster, and the response it should

provoke." They "can only have fascinated the author of Ulysses as

he watched established luminaries in an unedifying slugfest. .

. . All this, Joyce proclaims, will pass—and in the horse’s

case, will pass literally. It is withering, steaming

criticism."