"I don't want to see my country fall into the hands of German

jews either. That's our national problem, I'm afraid, just

now": Haines justifies his name

in Telemachus by spouting the theory of an

international Jewish conspiracy. Near the end of Nestor,

the proudly Unionist Mr. Deasy subjects Stephen to more of the

same: "England is in the hands of the jews. In all the highest

places: her finance, her press. And they are the signs of a

nation's decay. Wherever they gather they eat up the nation's

vital strength." Distrust of Jews has deep

historical roots in Europe, but in the late 19th and

early 20th centuries the new ideology of antisemitism was

filling people in Germany, France, Russia, Austria, Hungary,

and Britain with a very specific dread: that their nations

(both Haines and Deasy are fixated on that word, and the

fixation returns in Proteus, Cyclops, and Circe)

were being undermined by disloyal Jewish citizens.

In 1879 Wilhelm Marr (1819-1904) published a pamphlet which

Jacob Katz has called, in From Prejudice to Destruction:

Anti-Semitism, 1700-1933 (1980), the "first

anti-Semitic best-seller." The work was titled Der Weg

zum Siege des Germanenthums über das Judenthum (The

Way to Victory of Germanism over Judaism). The essence

of Marr's argument, Gifford observes, was that "Jews in

Germany had already taken over the press, they had become

'dictators of the financial system,' and they were on the

verge of taking over the legislature and the judiciary." Marr

did not invent these charges: they were already current in the

turbulent, disunified Germany of his day. Nor was he a racial

bigot in any simple sense: three of his four marriages were to

women who were at least partly Jewish, and he renounced

antisemitism and German nationalism toward the end of his

life. But by depicting two peoples (one native, the other a

foreign invader) locked in irreconcilable struggle, and by

describing a massive conspiracy to infiltrate and take over

the vital systems of one society, he provided an ideological

justification for bigotry.

A quarter century later, in 1905, Russian secret police

seeking to justify pogroms in the Pale of Settlement produced

the notorious forgery called the Protocols of the Elders

of Zion, which gave evidence that Jews were planning a

takeover of the entire civilized world. The Protocols

did not circulate in western Europe until the end of the Great

War, but Joyce anachronistically alludes to them in Circe

when Bloom's father "appears garbed in the long

caftan of an elder in Zion." A less anachronistic

inspiration for Haines's reference to "our national problem,"

and for Deasy's picture of Jews so dominating England's "finance,

her press" that they "eat up the nation's vital

strength," may have announced itself to the writer in

1905, when the British Parliament passed the Aliens Act. This

legislation, the first to impose controls on immigration into

the UK, appears to have been aimed particularly at the

multitudes of Jews who were fleeing Russian pogroms. Large

waves of Jewish immigration into England in the 1890s spurred

passage of the law.

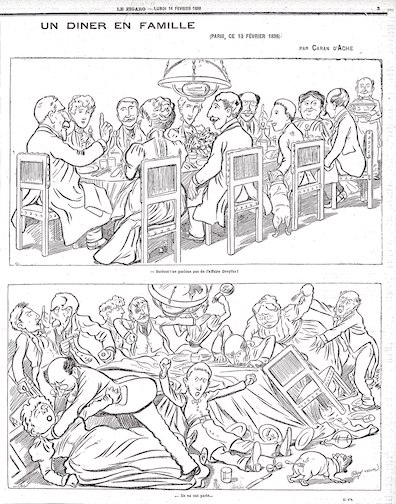

A comparably notorious expression of antisemitism had roiled

France in the 1890s when Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jew serving

in the French army, was convicted in 1894 on exceedingly

flimsy grounds of giving secret military documents to the

Germans. Many Frenchmen assumed that Jews felt more loyal to

their own international ethnic cabal than to the nation that

had given them citizenship. When new evidence emerged in 1896

implicating a different officer, the military command

suppressed the evidence, effected a hasty acquittal of the

non-Jewish officer, and brought new charges against Dreyfus

based on fabricated documents. Émile Zola published a

fiery letter titled J'accuse in a prominent

newspaper, stirring public pressure for Dreyfus to be

acquitted in a new trial. When the trial was held in 1899, a

battle for public opinion raged, led on the anti-Dreyfus side

by Édouard Drumont, publisher of an antisemitic newspaper

called La Libre Parole that had been slandering Jews

since 1892.

This reactionary response to the Dreyfus trials briefly

surfaces in Proteus when Stephen recalls Kevin Egan

talking about "Monsieur Drumont." No mention is made of

Drumont's views, but by dropping the name into the chapter

Joyce imports a French context for European antisemitism into

this novel. Haines, who has voiced suspicion of "German

Jews" in the previous chapter and whose name means

hate in French, probably represents another indirect

evocation of the Dreyfus affair, in which French bigots

defended their nation from a traitor who was ostensibly

working for the Germans. (Dreyfus was convicted once again in

the 1899 trial, but subsequently pardoned. In 1906, after

years of tireless labor by his brother and his wife, the

falsity of the charges against him was at last proved. He was

reinstated in the French army at the rank of major, and after

serving throughout the Great War retired as a lieutenant

colonel.)

When Haines voices antisemitic views in the first chapter, it

may seem that Joyce is characterizing them as a new import

from England, a parasite clinging to a "stranger." Deasy's more

detailed exposition of the ideology in the second chapter puts

an end to that slight comfort. Antisemitism is already well

established in Ireland and will surface many more times in the

book. The men in the funeral carriage in Hades,

Nosey Flynn in Lestrygonians, Buck Mulligan in Scylla

and Charybdis, Lenehan in Wandering Rocks,

and Bloom himself in Ithaca all indulge invidious

stereotypes about Jews, but it falls to the novel's

outstanding antisemite, the Citizen, to voice the suspicion

that Jews feel no loyalty to the nations that admit them,

unless perchance that country is "the new Jerusalem." The

Citizen insinuates that the many Jews trekking across European

borders are internationalist provocateurs: "What is your

nation, if I may ask?" Bloom, of course, answers that

his nation is Ireland: "I was born here. Ireland."

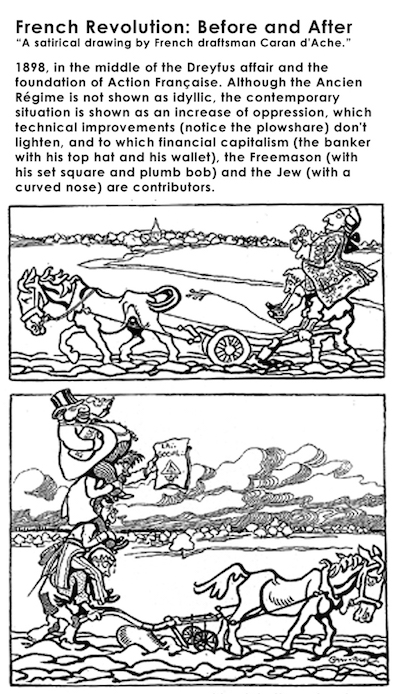

Antisemitism was certainly the strongest current in fin

de siècle suspicions that internationalist provocateurs

were undermining European nations, but other kinds of bigotry

played a part. Catholic countries like France and Ireland

regarded the international order of Freemasons, whose members

were mostly Protestant and whose beliefs inhabited a hazy

middle ground between religious mystery and secularism, as

threats more pernicious than any form of atheism. In a

personal communication, Vincent Van Wyk points out that Jews

were sometimes associated with Freemasonry, as in the second

cartoon featured here. Joyce happily added this second locus

of suspicion to his protagonist, making Bloom not only (ambiguously)

a Jew but also (far less ambiguously) a Mason. When Nosey

Flynn says that Bloom will never sign his name ("Nothing in black and white"),

he may be trotting out a stereotype about Jews, Freemasons, or

both groups.