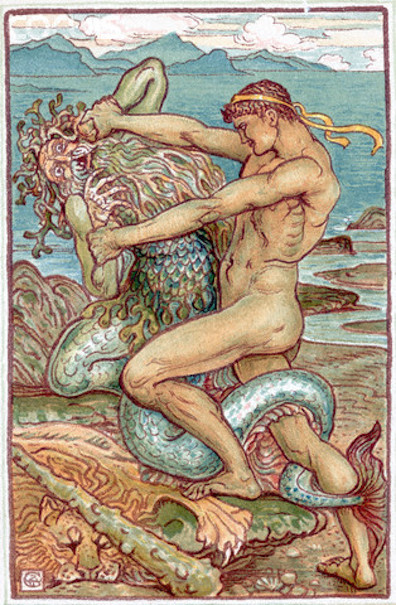

In Book 4 of Homer's Odyssey Telemachus has

traveled from Nestor's palace in Pylos to the hall of Menelaus

in Sparta, seeking information about his father. Menelaus

tells him that his journey back from Troy was interrupted when

his ships were becalmed off the sandy island of Pharos, north

of Egypt. Ignorant of which god might have stilled the winds,

and facing starvation, Menelaus was assisted by the nymph

Eidothea, daughter of the sea god Proteus. She told him that

the Old Man of the Sea might answer his question, if Menelaus

could capture him on the beach during his resting hour at noon and hold him fast

while he assumed the shapes "of all the beasts, and water, and

blinding fire." Following her advice, Menelaus ambushed

Proteus when he arrived to nap among his seals on the sand,

endured the transformations, and was rewarded with information

about the winds. He learned also of Odysseus' whereabouts on Calypso's island.

Joyce's chapter does not allude to Menelaus or Eidothea, and

it makes no reference to Proteus until very near the end, when

Stephen thinks briefly of "Old

Father Ocean." It does develop the parallels with

Telemachus. Stephen too has continued

journeying, from Deasy's school south of the Sandycove

tower to the Sandymount beach north of it. Stephen thinks

about his plan to meet Mulligan at "the Ship" at 12:30 (the ambush planned by Antinous

in Book 4), and he resolves not to return to the tower

(affirming his sense of usurpation).

He thinks briefly of his quest for spiritual fatherhood, and

both he and Kevin Egan observe that he resembles Simon

Dedalus, just as Telemachus resembles

Odysseus. At the end of the chapter he sees "a silent

ship" floating into Dublin on the tide, "homing," which

suggests Odysseus' stealthy return

to Ithaca.

But by far the most powerfully suggestive analogue to Homer's

story lies in Stephen's restless, relentless meditations on

change. Everything around him is in flux: the incoming tide,

the changing weather, rotting and rusting objects, burping

sewage gases, people and animals and ships and breezes passing

by. Language, his medium for contemplating the world, is

constantly shifting as English gives way to French, Latin,

Italian, German, Irish, Scottish, Spanish, Greek, Hebrew, and

17th century gypsy "cant." Memories flood in, taking him to

Paris, the slums of Dubin, his aunt's house in Irishtown,

Clongowes Wood College, the Howth tram, the Sandycove tower,

churches, an antiquarian library, a bookstore. Imagination

takes him to scenes of starvation, war, exile, and political

intrigue through all the long centuries. Stephen's internal

landscape too is shot through with change. He replays past follies and pretensions and obsessions and temptations, personal connections that have

helped make him who he is, an imaginary doppelgänger,

another self in a past life,

another self on a distant planet.

The human fear of change is rooted in the fact that life

itself is a transitory phenomenon whose accomplishments, joys,

and satisfactions are threatened by inevitable extinction. The

third of Leopold Bloom's chapters, a journey to the graveyard,

represents Bloom's unsentimental, irreligious contemplation of

mortality. The thoughts in Stephen's third chapter are very

similar. Everywhere he looks he sees death: the shells of

former sea creatures crunching beneath his shoes, a dog

rotting on the seaweed, the corpse of a drowned man surfacing

from its ocean grave, a midwife's bag containing a dead fetus,

bits of wood from the wrecked Spanish Armada, whales stranded

on the beach, Viking rampages, a murdered post office worker,

a buried mother.

It might be argued that all the changes filling Stephen's

consciousness align him with the Proteus of Homer's poem. But

the Linati schema associates Proteus with "Prima materia," the stuff

that Stephen is wrestling with, and identifying him with

Proteus would not take account of his struggle to find

answers. He seems more like Menelaus in his search for

enduring truths amid the flux. His first word, "ineluctable," implies a

desire to struggle out of the illusions of the sensorium into

apprehensions of absolute reality. He searches for Boehmian

mystical signatures,

Berkeleyan ideal signs,

Blakean primal faculties,

the Christian divine substance,

the Edenic paradise, the

Aristotelian "form of forms,"

the "word known to all men" that is love. He seeks the meaning

of a prophetic dream,

rejects attachments that smack of suffocation or entropy, rebukes himself for

the egotistical delusions

and false hopes he has

pursued. He yearns to be loved, to be properly known, to

accomplish the artistic work that he is capable of.

This thread of scrutinizing, aspiring, determined spiritual

search ties the chapter together, and although Stephen does

not acquire definitive answers as Menelaus does, he does enact

something like Menelaus' successful struggle. He stares down

his depressing family connections, his morbid fear of water,

his physical cowardice, his continuing attachment to Catholic

religion, his social and artistic pretensions, his

misogynistic distance from women, his alienation from all

others. A mood of hopefulness infuses the chapter, and becomes

stronger as it proceeds. It is the hope of someone who can

comically and freely accept the world as it is. In beginning

to see the adult he may become, Stephen is both Menelaus

holding fast to his vision of the god, and Telemachus growing

into Odyssean maturity.

As with Nestor, Joyce's two schemas disagree on the

time frame for Proteus, but in this case it is

possible to affirm one over the other. The 10:00 start

specified in the Linati schema probably would not allow

Stephen enough time even to finish

his meeting with Deasy, much less to travel all the way

from Dalkey to Sandymount Strand. And several details in the

text suggest that the hour of noon is approaching. The Gilbert

schema, having been composed later, may here reflect Joyce's

growing understanding of the temporal dimensions of his own

fiction.